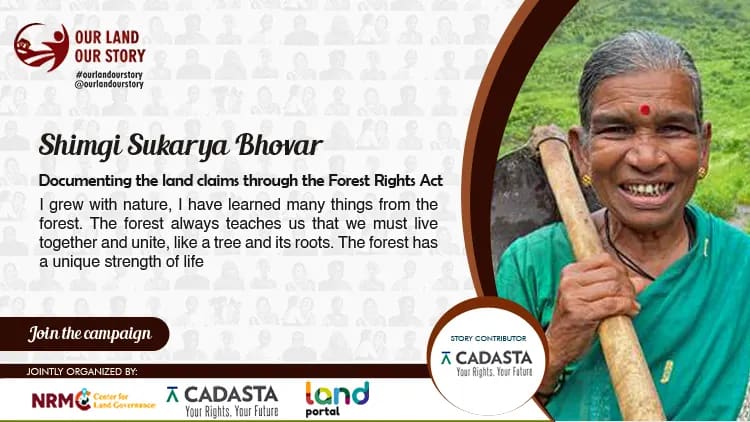

Documenting the land claims through the Forest Rights Act

Shimgi Sukarya Bhovar is a 60 year old mother of two from the Phanaswadi Village in Panvel Taluka, Raigad District of India. Shimgi’s life and livelihood are dependent on the forest surrounding her village.

Shimgi explains, “Our family used to work for wages on a farm controlled by a non-tribal landlord. One time there was a quarrel between the landlord and our family over the wages. The landlord sent men to kill my husband and our whole family, so we had to flee out of fear for our lives. As soon as we left the village, the forest and the hill saved us because the landlord and his men could not reach us through the dense forest and the high mountains. We reached the top and we thanked the forest and hill as well. Because the land we were cultivating was our only means of subsistence and if we tried to go back we would not be able to find work due to the landlord conflict, we left the village but did not leave the forest land. We came through the dense forest and mountain and continued farming. And today we have filed a claim for that forest land.”

Shimgi’s family depends on the forest to collect fruits, roots, and other vegetables, which grow naturally in the rainy season. A few years ago, her family started planting rice.

Commenting on the forest’s role in her life, Shimgi said, “I grew with nature, I have learned many things from the forest. The forest always teaches us that we must live together and unite, like a tree and its roots. The forest has a unique strength of life.”

But access to the forest and the longevity of those rights were not guaranteed for Shimgi or other members of her community. The communities lacked any form of formal records or proof of their communal and individual rights over the forest. To address this problem, Indian NGO Waatavaran partnered with Cadasta Foundation to map and collect geographic and demographic data for the Scheduled Caste and Tribal Communities living in the forests of Raigad District in Maharashtra State.

Shimgi explains, “My previous three generations depended on forests and agriculture. This was their means of subsistence. It was not only a means of livelihood but also the source for housing as our houses were built from the wood of this forest. But now some people told us that we have no rights on this forest land. When I heard that we have no right to this land, I felt afraid that these people would remove us from this land.”

She asked herself, “If we lose our rights to the forest, what would we eat? Where would we live? Where would our children play? Everything will collapse if we lose the forest. I am 60 years old now, but my grandson, where will he play?”

Using Cadasta’s training and tools, Waatavaran documented the forest claims to be submitted to local village councils for the first step of approval of their formal individual and community forest right titles under the Indian Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006. This act recognizes the forest rights and occupation of forest land by Forest-Dwelling Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest-Dwellers who have been residing in such forests for generations.

Commenting on the process, Shimgi said, “After the Waatavarn came into the village I personally changed my mind and now I am fully prepared to fight for my rights to the forest. I am fighting for the next generation. Fighting for this forest and mountain which have saved me. This is my home. I will never leave this land. I will fight for it because it is my right. We, the tribals, have claimed this land with the help of Waatavaran and we will definitely win.”

Once Shimagi’s claim is approved, including her as well as her family’s rights, to manage, cultivate, and live in the forest will be protected by the Indian Forest Rights Act, providing them with a secure place to live and work for generations.

Story Contributor: