“Women & children should never find themselves marginalized and exploited at the hands of a failed system.”

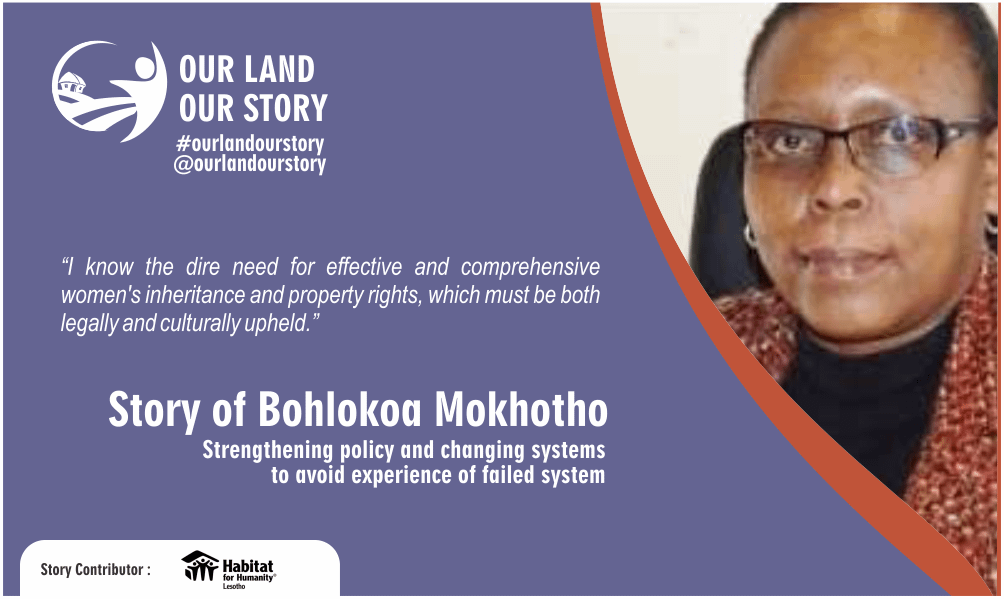

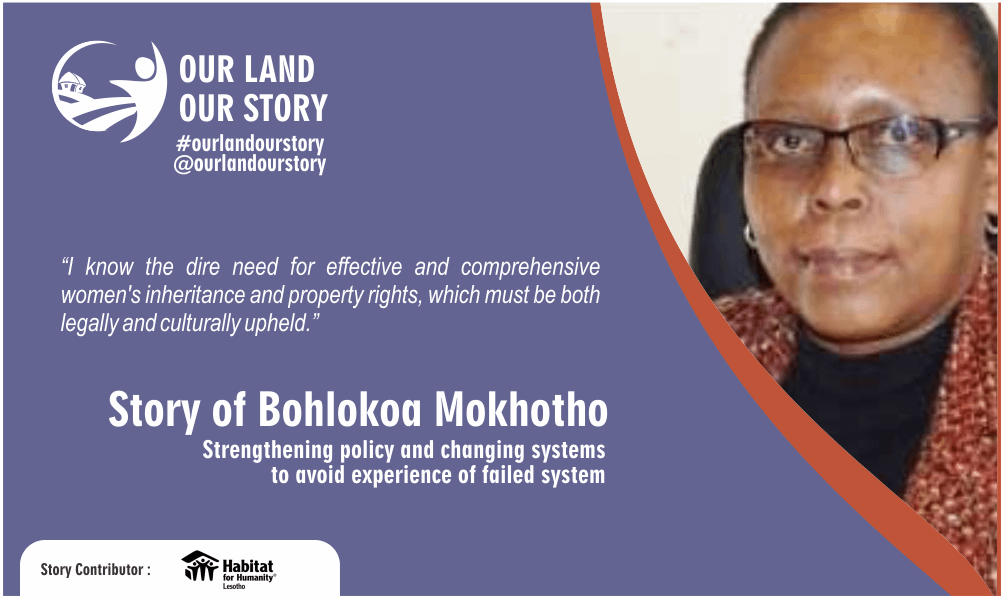

Bohlokoa Mokhotho , advocacy specialist in Habitat for Humanity Lesotho, shared her personal story of disinheritance, which, speaking from her experience, can affect any widow regardless of her background. It can also affect widows from all spectrums of life, despite legislation aimed at protecting the marginalized. For example, some of the major legislation changes in Lesotho are the amendment of the 1992 Inheritance Act, the 2006 Legal Capacity of Married Persons’ Act, and the 2010 Land Act – all seeking to ensure that women have a right to influence decisions that affect their lives. Even with these laws, however, disinheritance, property grabbing, and evictions still exist in Lesotho, and Bohlokoa was a victim of disinheritance following her husband’s passing in 1995.

On the first of January 1989, Bohlokoa and her husband were married, and their possessions were merged into a singular estate. They were blessed with two beautiful girls soon after. Their first daughter was born in 1989 and our second in 1992. Sadly however, their eldest daughter passed away from a car accident, and a few years later her husband passed, again as a result of a car accident. With no time to mourn, Bohlokoa was disinherited immediately after her husband was laid to rest.

Bohlokoa and her husband had begun building what was meant to be their dream house for their family but following his passing she was immediately isolated by my in-laws and her world was upheaved. All movable and non-movable property was taken from her. Going to the police was fruitless, and Bohlokoa resorted to the courts of law, which appointed her as executor of her late husband’s estate. She believed that this would bring an end to her woes, but her father-in-law contested the appointment, claiming that the family held a meeting – in her absence of course – and agreed that he was the rightful heir of her late-husband’s estate. He fraudulently issued a letter by a brother of one of the principal chiefs – in the chief’s absence – affirming this claim. Bohlokoa’s in-laws confiscated all the building materials from the building site, and, sadly, the police and courts of law failed to act.

Realizing that she was fighting a losing battle as the matter was becoming too sensitive and complex – due to the involvement of bribery and corruption in addition to lack of support from legal institutions – Bohlokoa figured it was best to let go. As the sole surviving parent to a 3-year-old daughter, Bohlokoa had to make a choice: “Do I keep on fighting a losing battle putting my life at risk? Or should I just give up preserving the little I have and being the sole survivor of our baby girl?” She made up her mind, and gave up, for it seemed too much for her to take on. As young as Bohlokoa was, she could not put my life at risk to secure my assets. However, given a different scenario with sound support structures, she might have thought otherwise.

As a widow living in Lesotho, Bohlokoa says “I know the dire need for effective and comprehensive women’s inheritance and property rights, which must be both legally and culturally upheld. Women and children should never find themselves marginalized and exploited at the hands of a failed system. Habitat Lesotho is actively engaged in Habitat for Humanity’s Solid Ground global advocacy campaign improving access to land for shelter, and, as a part of the campaign, I play a part in strengthening policy and changing systems so that women in Lesotho will no longer share my experience.”

Story contributed by Habitat for Humanity Lesotho